With so many options, it’s hard to understand where you should start, moreover, it’s hard to know if you’re on the right track which is why I’ve compiled a list of tips for you.

The best songwriting tips are

1) To practice daily using popular chord progressions

2) To learn songwriting structure, ie, ABABCB

3) To understand diatonic, non-diatonic scales, and modes

4) To use loops, samples, and drum loops for inspiration

5) To not overcomplicate it

6) And to record yourself

1) Practice Using Popular Chord Progressions Every Day

Frankly, if there is one tip on this list that you should start implementing right away, it’s this one. Using books like Jazz Chord Mastery, Guitar Chord Progression Encyclopedia, and Chord Progressions: Pick Up and Play, you have at your disposal hundreds of common progressions that people still use in popular music today.

The usefulness of this is almost beyond comprehensibility.

By using common chord progressions as a foundation on which to build your own songs, you can learn so much about not only songwriting but also harmony, rhythm, voice-leading, the importance of simplicity (but also an appreciation for complexity), or even marketing.

Simply put, the best way to learn how to write songs is to learn some of the most popular chord progressions and start making your own.

If you’re familiar with self-help coaches at all, you’ll know that they commonly refer to the Pareto principle, which is, in layman’s terms, the idea that 90% of the output comes from 10% of the input.

It’s also called the 90/10 rule, and when it comes to songwriting and music production, making chord progressions and songs every day is that 90% action that’s going to make you a good songwriter. This is why I compiled a fairly large list for you:

| Progression in Roman Numerals | Chords |

|---|---|

| I-IV-V | F, B♭ and C |

| I-vi-iv-V | C, Am, F, G – 50s Progression |

| I-IV-VI-IV | C, F, Bb, F |

| iii-V-ii-I | C♯m, E, B and A |

| i-IV-V | F♯m, B and C♯ |

| i-V-IV-III | Am, G, F, E – Andalusian Cadence |

| I-IV-IV | E, A, and B |

| iv-♭VII⁷-I | Dm, Bb7, C – Backdoor Progression |

| I-V-VI-IV | D, A, B and G |

| I-V-VII-IV | A, E, G, D – Chromatic Descending |

| VI-III-I | E, B and G |

| vi6-ii-V6-I | Am6, Dm, G6, C – Circle Progression |

| V-ii7-I | D, Am7 and G |

| I-V7-IV7-IV7-I7-V7-I7-V7 | C, G7, F7, F7, C7, G7, C7, G7 – 8 Bar Blues |

| I-V-IV-vi | C, G, F and Am |

| I-IV-V-vi | G, C, D and Em |

| III-II-I-VI | B, A G F♯ |

| I-V-VI-IV | D, A, C and G |

| ii-IV-I | Dm, F and C |

| VI-V-IV-I | D, C, B♭ and F |

| ii-V-I | Dm, G, C – Common Jazz Progression |

| I-V-IV | D, A and G (drop D version) |

| I-IV-V | A, D and E |

| V-IV-I | D, C and G |

| I-IV-vi-V | D, G, Bm and A |

| I7-IV7-ii7-V | C7, F7, Dm7, G |

| I-V-vi-iii-IV | E, B, C♯m, G♯m and A |

| I-III-IV-VII-IV | D, F, G, C and G |

| I-III-IV-ii | D, A, G and Em |

| vi-I-V-IV-II | Em, G, D, C and A |

| I-II-III | D, E♭ and F (drop D) |

| i-V-II-VII | Asus2, E, B and G |

| vi7-ii7-V7-i7 | Am7, Dm7, G7 and Cm7 |

| I-V-vi-IV | C, G, Am, F |

| vi7-II7-V-I | F♯m7, B7, E and A |

| VI-v-i-VII-i | F, Em, Am, G and Am |

If you just practice making songs every day including how to add your own creative flair and spin to the most common chord progressions, you’ll come away as a far superior songwriter and musician.

And the fact of the matter is, nobody else is doing this. No one else has the perseverance, the dedication, and the work-ethic to make something like this a regular part of their day. Use the chart above to help you.

2) Learn Popular Songwriting Structure

Over the last few decades, songwriting has changed a lot. A big part of the reason why has to do with the various changes in the music industry like the explosion of streaming, just to name one. There was a time when a song would only have 1-2 songwriters attributed to it, despite the fact there may have been many contributors.

Those days are over, and now, many tracks will have 6-12 songwriters simply because anyone who contributed an idea will get credit, but that’s neither here nor there.

The fundamentals of songwriting structure have changed as part of this development toward streaming and away from the long-play (LP) record (although, there’s still a market for vinyl).

There was a time when a song would have the following structure or a structure that looks something like what you can see below. Understanding the basics of songwriting, especially the arrangement, is probably the fastest way to make songwriting easier.

What Are The Basics of Songwriting?

Introduction

- The goal here is to introduce the song. You can do it in any number of ways, including with a sample, a loop, a quote, or even a clip from an old TV show.

Verse

- The verse, like the chorus, is repeated multiple times throughout the song. However, the verse is of secondary importance, and it often has different lyrics in each verse, albeit, in a similar pattern.

Chorus

- Commonly the most important part of the song, the chorus is meant to be the hook, the part of the track that people hum along to and remember. The catchier it is, the better.

Verse

- The second verse will often have the same melody and structure as the first verse, but as I said above, it’s not uncommon for there to be a slightly different theme, or maybe even a different instrument in there the second time around.

Chorus

- The chorus will be heard again, similar to the verse in many cases, in a slightly different way but usually the chorus is the same every time. It’s the hook. It’s important that it keeps the listener’s attention.

Bridge

- A practically extinct part of songwriting but worthy of mentioning nonetheless, the bridge is the part of the song that diverges from the rest of the track, often both lyrically and musically.

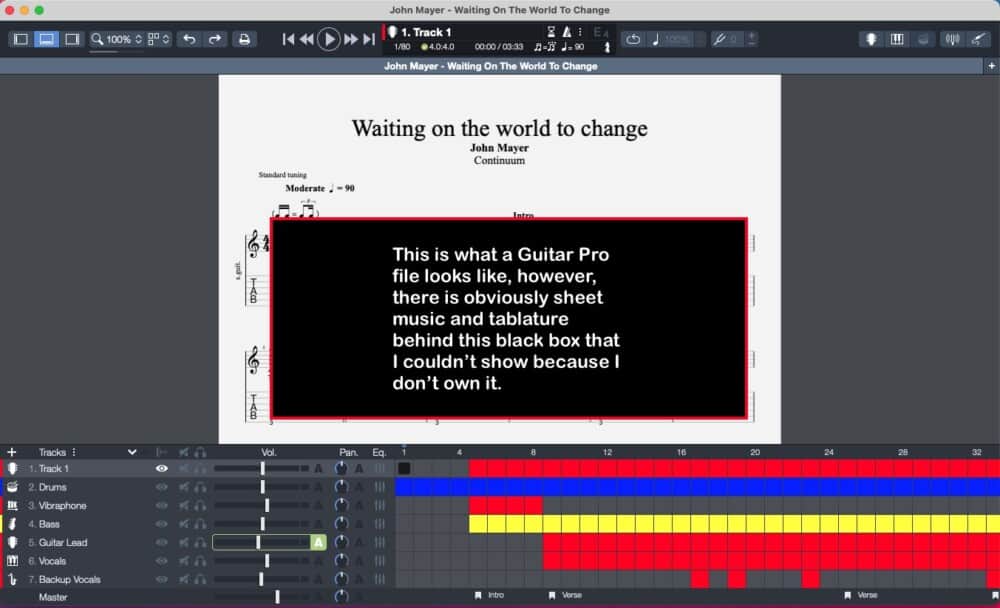

A great example of a bridge is the 1:49 mark of the song, “Waiting On The World to Change” from John Mayer, which is coincidentally a great example of this same structure I’m talking about, except with one less chorus.

Chorus

- This is the last time the chorus is heard, and there may be some kind of element to signify that. For example, there might be a horn section or something similar to hint that the song is coming to its end.

Outro

- The outro is kind of like saying “goodbye” rather than “hello” as what’s done in in the introduction. In metal, rock, and punk, for example, the outro is usually the sound of the guitars slowly fading out.

This is also called the ABABCB structure.

Understand that there are many small variants of this same song structure. It’s also worth mentioning that nowadays, the songs have gotten a lot shorter, usually between 2-3 minutes compared to songs like “Stairway to Heaven” that’s over 8 minutes in length.

A number 1 hit would never be that long anymore, in fact, the idea of a song being that long is practically laughable.

Additionally, songs in the modern era commonly don’t have a bridge especially trap and hip-hop songs which typically feature the same beat, rhythm, and melody repeatedly throughout the song without much variation (I have a guide on how to make this style of music, by the way).

Although, the arrangement of some of these so-called “simple” songs can be quite sophisticated.

3) Understand Diatonic and Non-Diatonic Scales

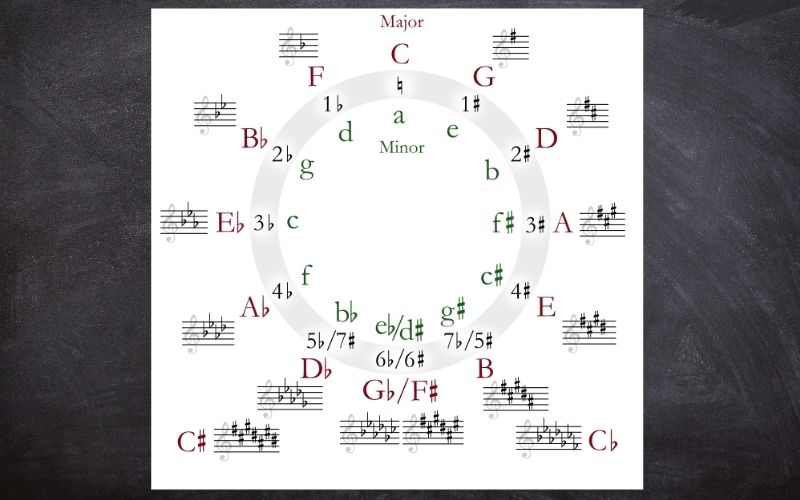

Diatonic scales are scales that have seven notes, each note is in sequential order, and they use even pitch letter names, A, B, C, etc., with five whole tone intervals and two semitone intervals. The semitone intervals are separated by two and three intervals, making up the whole key.

There are many diatonic scales, including all seven modes. A non-diatonic chord would be the opposite of this and use notes not found in the same key or sequential order.

So let’s back up from that and explain what it really means. A diatonic scale, put simply, is just a pattern of notes consisting of five whole steps and two half-steps within an octave.

It belongs to a particular scale and key signature. For example, C, D, E, F, G, A, B and C are all part of the C Major Scale, which is the diatonic scale to end all diatonic scales. It’s the scale on which the rest of Western music theory is based.

Note:

This is the order of whole-steps (tones) and half-steps (semi-tones) of the main major/diatonic scale.

W-W-H-W-W-W-H

Apply this order of steps and half-steps to any starting note, and if you count up from there in the relevant steps, you’ll get a Major scale.

A non-diatonic scale is a scale that uses notes that are outside of the pattern, key signature, or scale. For example, the whole-tone scale is a non-diatonic scale because the notes in a C Whole Tone scale, for example, aren’t part of any key signature or diatonic harmony.

A whole-tone scale, by definition, is a scale made up of a bunch of whole tones which means it’s non-diatonic because it doesn’t have five whole steps and two helf-steps.

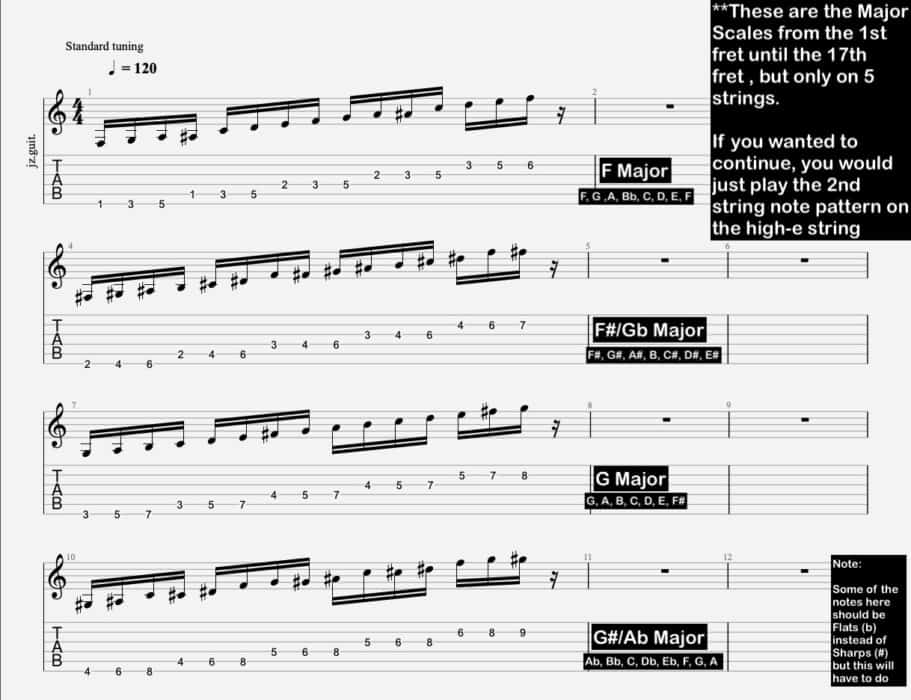

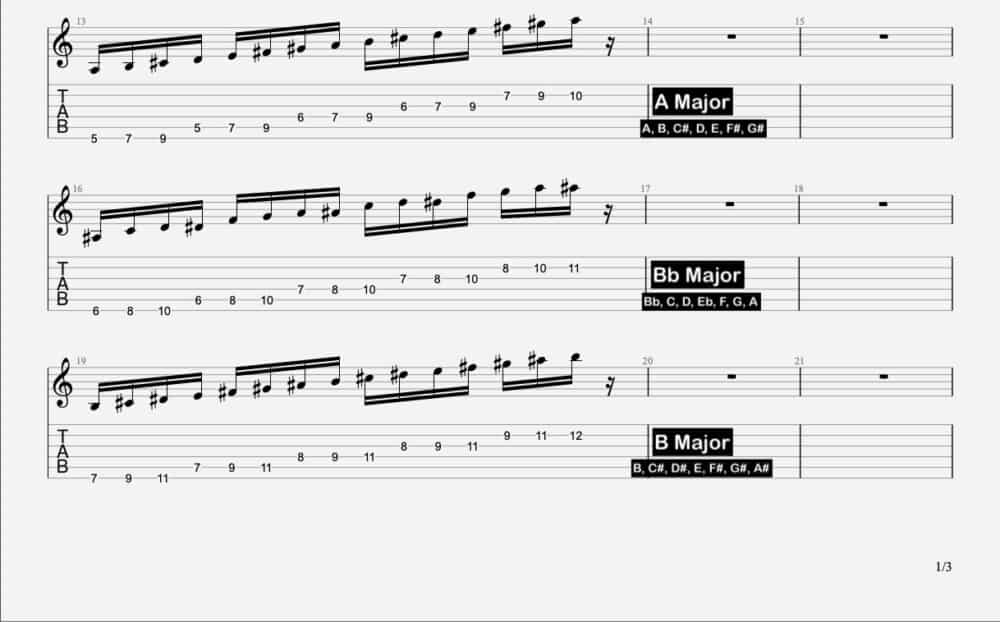

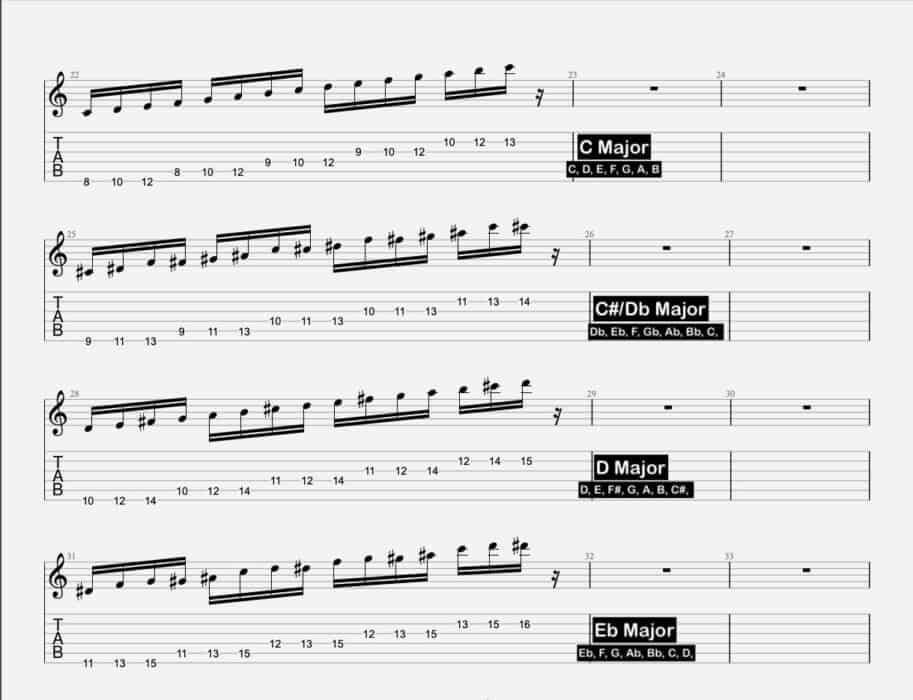

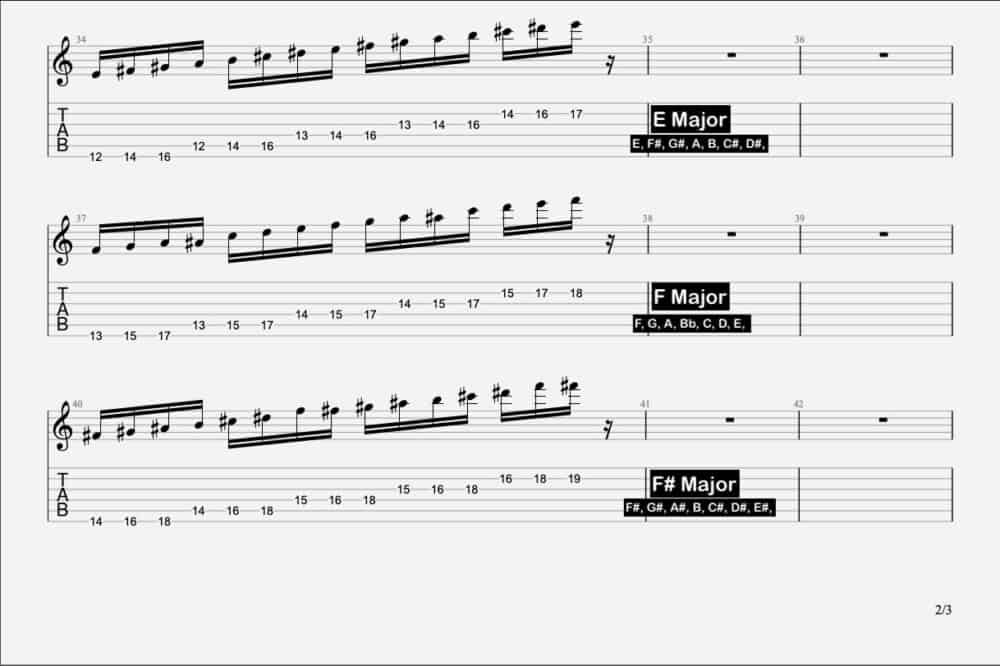

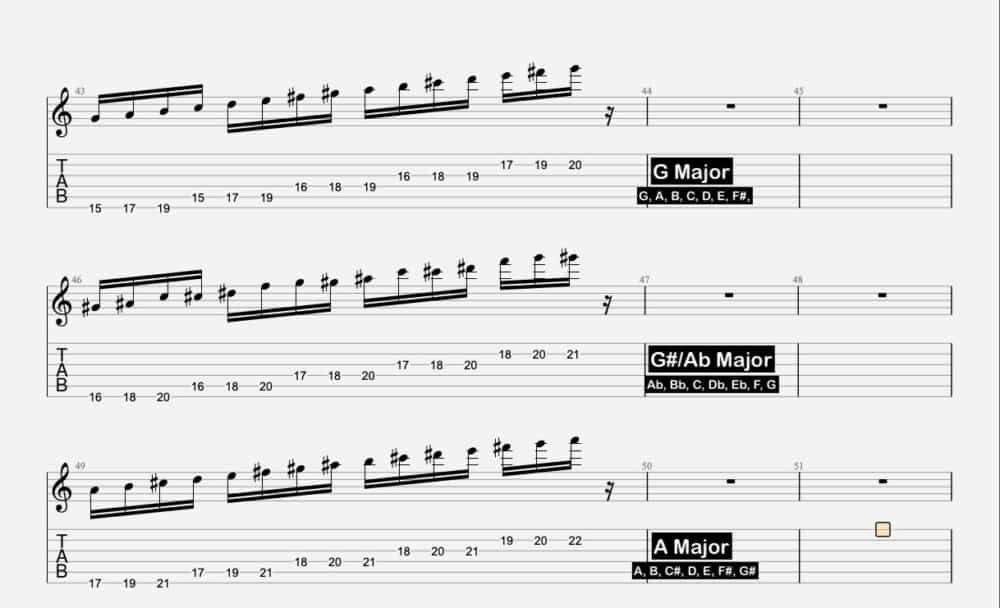

Here’s a list of all of the major scales in every key on the guitar using just five strings (they’re in standard notation as well in case you’re using a different instrument). After that, I’ll give you a brief run-down of the modes.

Note:

Sorry, the images ended up being a bit small. Zoom in on your computer or flip your phone on the side

F Major to Ab Major

A Major to B Major

C Major to Eb Major

E Major to F# Major

G Major to A Major

So where do modes come into play in this? What is a mode?

4) Understand The Modes and How to Use Them

Modes are a valuable and essential tool for any musician and I’ve talked about them before in my dedicated guide.

There are seven modes, and they all originate from the major scale. If you can remember the interval pattern of the major scale, aka Ionian Mode, you can count out all the other modes; it’s really that simple.

The major scale is also called the Ionian mode, and, as I said earlier, it’s the basis on which the rest of Western music theory has been created. It’s extremely useful to understand it because then every other scale, mode, or even chords for that matter, will suddenly make a lot more sense.

Buying Mark Sarnecki’s Complete Elementary Rudiments as well as the Answer Book is a great introduction to the basics of music theory.

It doesn’t take that long to complete, and by the time you’re done, you’ll have a very good understanding that way you’re no longer taking shots in the dark. A simple way to learn modes is by remembering a few things, however:

A) Remember the Pattern of the Intervals for the Ionian Mode (Major Scale)

W means a whole step, and H means a half step. Depending on your instrument, even the voice, you’ll have to understand where to find these intervals.

For the guitar, each fret equals a half step, and two is the equivalent of a whole step. There are five whole tone intervals and two half-tone intervals. The pattern goes like this W W H W W W H

So, if we were to start on the low E string and play the 3rd fret, that will be a G. When I use the Ionian Mode pattern counting from the G, I get G, A, B, C, D, E, F#, and back to G.

B) Remember the Order of the Modes

Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian. Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, Locrian.

You can do this by anagram if you need to. A lot of people use the following:

I Don’t Play Like My Aunt Lorie

or….

I Don’t Punch Like Muhammad Ali

…the latter of which omits Locrian, but it’s pretty much useless anyway, or at least I haven’t figured out how to use Locrian. I never bothered using an anagram. I just remembered them because they’re cool and I find them fascinating and easy to remember.

Take a look at my comprehensive guide on modes because this whole article could be all about them. Now that you know how to find them play around with them and listen to how each differs from another.

A beginning guitarist probably already knows the major and minor scale. The minor scale is the 6th degree of the major scale, also known as the Aeolian Mode (Natural Minor Scale), so that should be a great place to start.

C) Know the Tonality of the Modes = Major and Minor

Using the modes can really enhance your playing and songwriting because it gives you a toolbox of vibes. For instance, the seven modes can be broken down into two categories. 1) Major and 2) Minor.

The major scale or Ionian Mode can be played well with two other modes, the Lydian and Mixolydian. The remaining all play well over the Minor chords. Try them out and practice remembering which one goes with which scales.

1) Major Modes: Ionian, Lydian, and Mixolydian

2) Minor Modes: Dorian, Phrygian, Aeolian, and Locrian

| Mode | Vibe/Sound/Characteristic |

|---|---|

| Ionian | extremely happy and bright |

| Dorian | chill, bluesy, and emotional |

| Phrygian | evil and malevolent |

| Lydian | spacious, triumphant, and victorious |

| Mixolydian | sounds like the band AC/DC |

| Aeolian | sad, depressing, or dark |

| Locrian | dissonant, bizarre, or weird |

D) Figure Out A Way to Practice Them

Memorizing the mode shapes on the guitar is a great way to not only practice your technique, but it also gives you a better understanding of the instrument in general.

I’ve talked about this before on my other site, Traveling Guitarist, but what you want to do is just memorize the major scale in all 12 keys, and then learn the 6-string mode shapes.

This is a great way of going about it. Now, if you actually want to use modes to construct songs, then the better option is to treat the mode as a scale and then build chords from the notes. So what does that look like? It’s pretty straight-forward to be honest.

Let’s use B Dorian: B, C#, D, E, F#, G#, A…

….which is the 2nd mode of the A Major Scale

Those are the notes, so then you just construct triads out of them:

B, D, F# = B Minor

C#, E, G# = C# Minor

D, F#, A = D Major

E, G#, B = E Major

F#, A, C# = F# minor

G#, B, D = G# Diminished

A, C#, E = A Major

Playing Bmin/Bmin7 and A Major over and over again would create a very Dorian tonality, assuming that you played A, B, C#, D, E, F#, and G# over those chords, and you made B Minor the tonal center, and not A Major.

Remember, B Dorian is just the second mode of A Major. So if you play the notes of A Major over that progression, it’ll sound Dorian, like what you can hear in the video below:

Here’s how I showed them on my other site, Traveling Guitarist. This is how I practiced them when I first started. I did the same thing when I wanted to learn how to play the Harmonic Minor modes as well, and while maybe it’s not the best way to learn, it worked fine for me.

Ionian (Scale starting on root note): The Ionian is the same pattern, vibe, and look as the Major Scale. They’re the same, in practice, however, we use different terminology to describe them depending on what purpose we’re using them for.

Dorian (Which starts on the 2nd note, D, at the 10th fret):

Phyrgian (Which starts on the 3rd note, E, at the 12th fret):

Lydian (Which starts on the 4th note, F, at the 13th fret):

Mixolydian (Which starts on the 5th note, G, at the 3rd Fret):

Aeolian (Which starts on the 6th note, A, at the 5th Fret):

Locrian (Which starts on the 7th note, B, at the 7th Fret):

5) Write At Least One Song Per Day

You’ll get in the habit of creating daily, and if you want a career in music, this is where it starts. Don’t go hard on yourself if you accidentally miss a day or you get off track. Just remind yourself why creating is important to you and why you want to write songs. You’ll get back on track and have great ideas flowing in no time.

Songs do not have to be complicated, so doing a simple I-IV-V chord progression will do just fine, as long as your melody on top is interesting and memorable. Writing in any key and mode will do, as long as you are using them in a way that sounds good to you. Chances are that if it sounds to you, it’ll probably sound good to someone else.

A great way to make a song feel complete is to add parts to the song like bridges, transitions, intros, and outros. Verses and choruses are a given, but changing things up can get as complicated as you want.

For example, try an intro and outro that are the same, add chord progressions for the chorus and pull back on the verses. It’s interesting enough, and you are adding dynamics that could sound cool. A great tip is to use weird chord extensions too.

Try anything and everything. If it doesn’t work, you’ll know, and you can replace it with something that fits better. If one song per day seems like too much, try a full arrangement or lyrics, or keep working on recording demos as best as you can.

You’ll soon gain more knowledge on recording and songwriting if you take it seriously, which will give you the mental stamina to start writing one song per day.

Use my guide on how to write a song in 10 minutes to figure out how to lay a song down quickly, moreover, my article on creating a song without instruments is going to help you a lot as well.

6) Use Loops, Samples, and Drum Loops for Inspiration

Creative people get inspiration from just about anything. Musicians and those who aspire to write music are part of that creative group, so they are also prone to not knowing where to start, or they may perceive themselves as having writer’s block from time to time.

Personally, I don’t believe in writer’s block. All that means is that you’re setting far too high of standards on yourself.

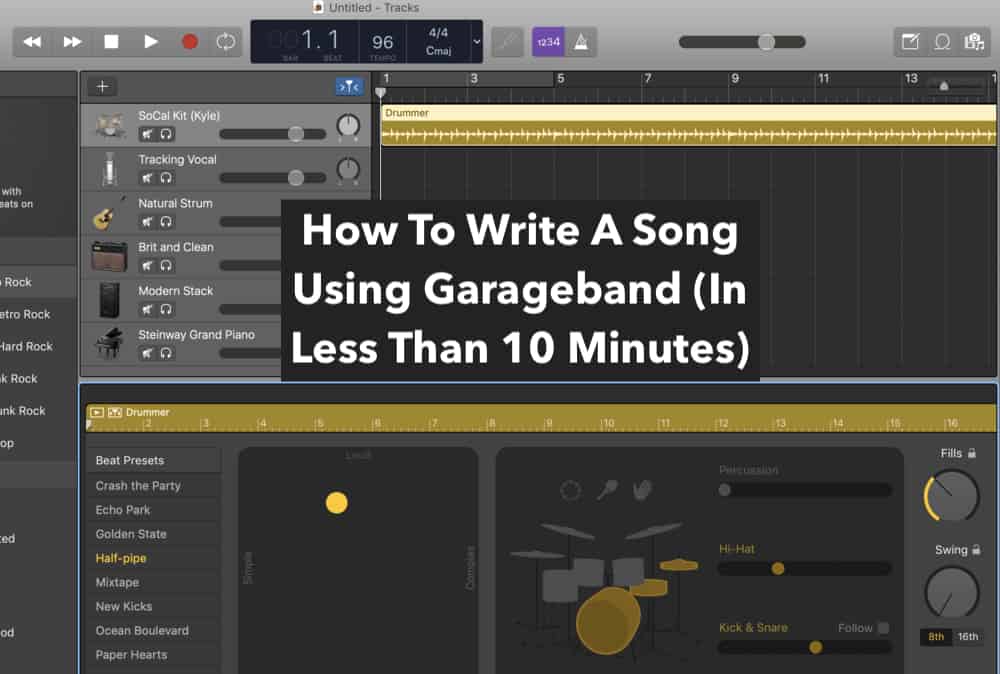

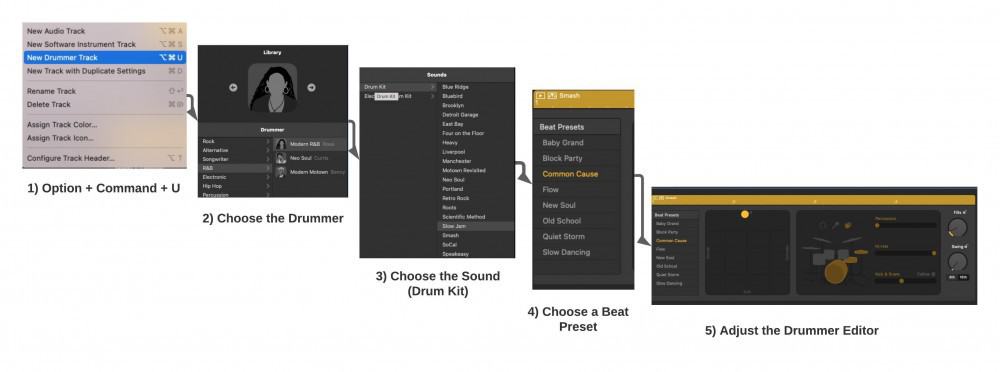

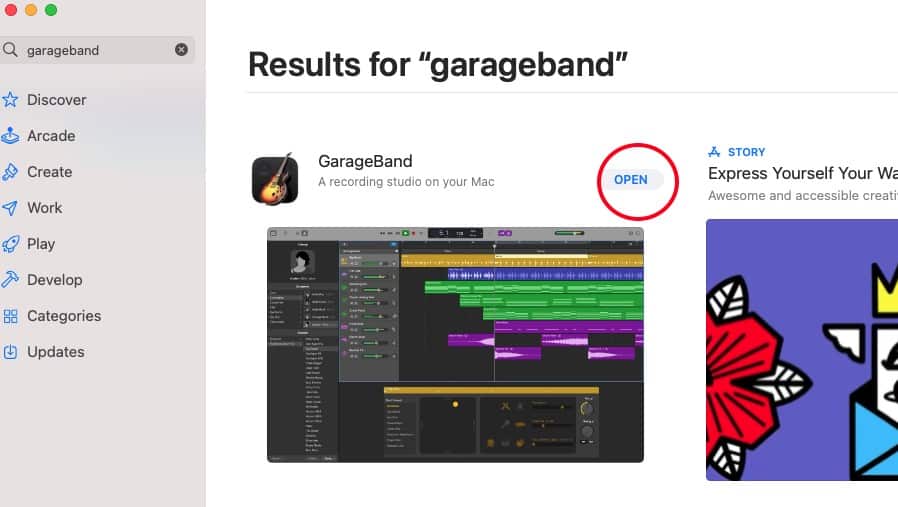

If you have access to a DAW like GarageBand or Logic from Apple, there are many ways to jump-start the creative process like loops, samples, and drum simulators.

Using loops, samples, and drum loops is common practice for musicians that don’t play those particular instruments or don’t have access to them to create music and this is a great way to speed things up as well.

The fastest way to write a song (under five minutes or less), is to understand the basic songwriting structure, ABABCB, and to use loops, drum loops, samples, and popular chord progressions.

You can use the loops that are provided by the software (more on those in my guide), or you can download them from another site like Loopmasters.

Be aware that you may not be able to monetize your songs on platforms like YouTube or Facebook. Check the user agreement here if you have questions about how you can use loops or samples in your original music.

In many cases, they are royalty-free, but you can’t monetize them on certain platforms which I’ve argued elsewhere before including in my latest sampling guide. A safer bet for using loops and drummer AI is to just use Garageband’s Drummer Track (also my tutorial) as well as the Apple Loops.

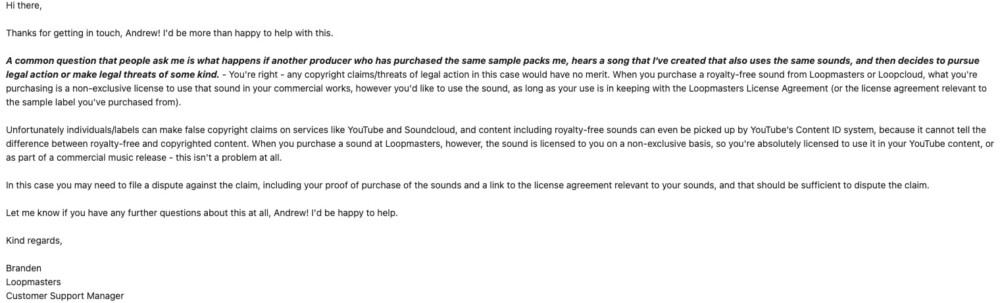

In the case that you run into a nefarious actor who tries to DMCA takedown your material because you used the same loops, take the words of wisdom from Branden here and understand that there is no legal merit for them to do so.

Proving that you’ve been authorized to use the loops/samples is enough to have YouTube bring the content back up if you’ve been targeted by one of these n’er do wells (turn your phone sideways to see the image below better).

7) Don’t Over Complicate Things (Trust Your Ear)

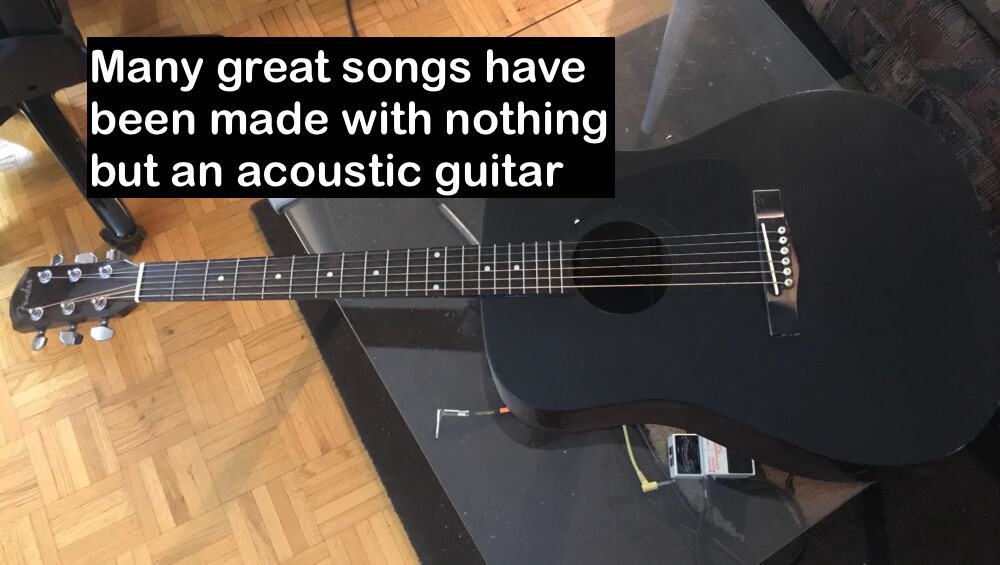

Overcomplicating things only makes life more complicated, I think we can agree on that; and music is the same. There are infinite songs that are made of only 2 to 3 chords in the entire song. Many notable singer/songwriters have said you only need three chords and that’s the truth. It’s a great rule of thumb to follow.

Many bands use simple bar chords, mainly because they are easy, they sound full, and many musicians don’t know how to make more interesting chords (nor do they need to). This kind of playing is ok, but eventually, you’ll want to learn more dynamic chords for writing (or you may not).

Techniques like great phrasing and open tuning will make a massive difference in your songwriting too, but they don’t necessarily have to be on the first song you ever record. Take it easy on yourself. Otherwise, it will be your last recording because you’ll be too much of a perfectionist to ever make and release anything.

8) Use a Metronome, Garageband’s Drummer Track, or Drum Loops

A vital part of being a musician is being able to play on time. No matter what instrument you play, the song keeps playing, and you need to be in time to play with the other members.

If you don’t have a drummer to play with, a metronome like this one is perfect to practice with. It’s important to get comfortable playing your instrument or singing to a metronome or a drummer that can keep time well.

If a drummer is on hand, let them play to the metronome, and you play or sing on top. The beat of the metronome should disappear if your drummer is in time. If not, you’ll know right away because you’ll hear sporadic metronome beats.

If you are playing and singing, start with practicing just playing over the drummer with your instrument, don’t sing just yet until the playing feels like it can be on autopilot, then slowly work in your voice.

Take it slow and concentrate on being a solid player first who can play on time. If you want your musical ideas to truly sound good, you should be able to play the song with the accompaniment of another musician or a rhythm section like a drummer.

Again, Garageband’s drummer track is great for this. Rather than use a boring metronome to play along to, you could use drum loops, AI drummer tracks, or you could even jam along to a backing track.

Just make sure you record yourself as well because you want to know what your playing actually sounds like. It’s easy to be a hero in your own mind sometimes.

9) Always Record Yourself Playing For A Couple Reasons

A) Record Yourself So You Don’t Forget Riffs and Ideas

This is an excellent tip for anyone, not just beginners. We often find ourselves in situations where we forgot a lyric or a melody, and the best way to not let that happen is to record it before it escapes your mind.

Thankfully, nowadays, you can voice command your voice recorder to start recording instantly on iOS. I use this all of the time, in fact, I just used it once while I was making this article.

Currently, I’m using an iPhone 7 + (I recommend getting the newer ones though), and I often use the Garageband iOS application to quickly record riffs, loop them, and then jam along to them if I’m too lazy to turn on my amplifier and use my BOSS RC-5.

Voice recorders on your phone or computer can be sufficient for this task if you are humming a melody or a series of lyrics. They can build into a whole song before you know it, but if that initial idea gets derailed somehow, you will regret not remembering your starting point. Record the idea and play it over and over on a loop until more ideas come out.

B) Record Yourself So You Actually Know How You Sound

This is probably one of the most important tips that anyone could ever give you. I’m guilty of playing the guitar for years by myself in my room and never, ever recording myself. Once I finally started doing it, I realized how awful of a guitar player I really was.

A better way of putting it, is that I was a great guitar player but a terrible musician. If you want to record yourself, use your smartphone or connect your instrument with a Scarlett 2i2 like I explained how to do in my guide for plugging in your guitar.

Use this guide instead if you need to mic an instrument. Or just watch the short video here:

10) Build on Your Ideas

A common mistake that beginning songwriters make is trying to put all the tricks into every initial idea. While that’s easy to say, it’s much more frustrating to pull off unless you already have a good idea of how to play an instrument or you have a lot of experience producing already.

In that case, you already understand that starting small and building on the basics can fast-track your progress.

Start with a melodic or rhythmic idea that sounds good to you, then add some dynamics like fills or key changes that give it more character. The next step would be to make an arrangement and work out the parts, piece by piece, adding and taking away what is necessary for the song to be memorable and enjoyable.

When you get a solid foundation, bring in another player like a drummer or bassist that can help bring out the best in your arrangements.

What is suitable for the demo isn’t always good for the live song. Meaning, if you think your song is perfect because you can play it or sing it well, it doesn’t always mean your band can perform it just like it is.

They may need to change things, and that usually adds more dynamics. It can be a great writing tool to bring in other players.

11) Understand Harmony and Melodies for Songwriting

What’s Harmony?

Simply put, the difference between harmony and melody is that if notes are played harmonically, they’re played together at the same time, whereas if they’re played melodically, they’re played separately and in linear and progressive fashion. A chord is a harmony, and a melody is a singing voice, for example.

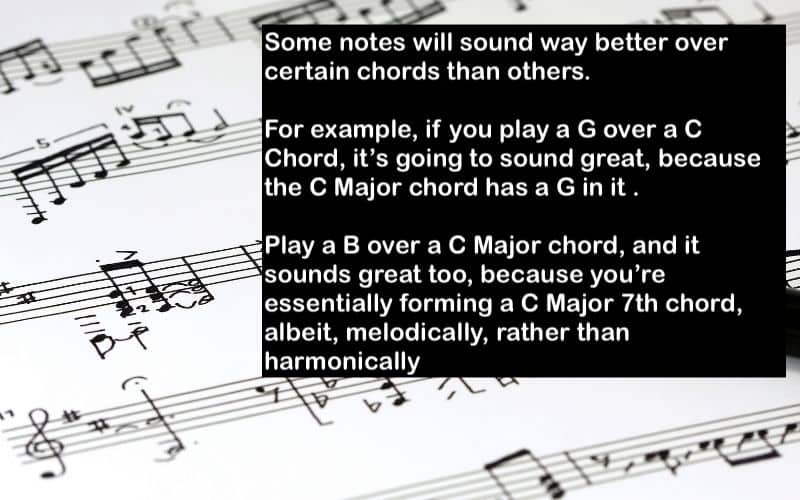

The study of harmony can get complicated but you don’t need to be Beethoven or Bach to understand the most basic of harmony. The text in the image above is a great example.

If you play a D Minor chord over a C Major chord, it’s probably going to sound pretty cool because both of those chords belong to the same key. That’s a harmony.

Harmony is the musical balance between two or more instruments, including voice. With harmony, it doesn’t matter what instruments are playing, as long as there is harmony amongst them. Without proper harmony, you could have dissonance and parts that don’t exactly sit well with the listener.

The best way to understand harmony is to understand what the key of a song is. If you are in the same key, you’ll always be in harmony with the other instruments.

Some notes feel better than others in a key, but there won’t be as much dissonance if you’ve played notes in the scale. The key of a song is the primary note on which the rest of the music is based.

Harmony is distinguishable from melody and rhythm, so it’s going to stand out if it’s off. When all parts are playing notes of the same chord, it’s called a consonant chord, and the opposite is a dissonant chord.

Consonant chords sound like they fit, where dissonant chords do not. Try sticking to consonant chords when possible, or at least until you’ve really grasped what you’re doing.

What’s Melody?

Melody in songwriting is one of the most important things to understand. With a bad melody, you don’t have a memorable song. It may have a great rhythm and harmonizes well, but if it’s easy to forget, it’s not going to do you any good.

Melodies fit songs best when they are in the same key as the song, just as harmony works best as a consonant with the melody.

It all goes hand in hand to create a pleasurable experience for the listener. Understanding conjunct melody and disjunct melody is important because you don’t necessarily have to use a wide range of notes, like in disjunct melodies, to create a great melody.

Just start recording yourself humming or picking a melody you think has potential and build on it. If you start with single notes and move to chords, you’re going in the right direction.

The key is to create and be creative; I think that’s why most people enjoy songwriting so much, it’s a great creative outlet. Try not to overthink it either.

Even the terminology “conjunct” and “disjunct” might be too confusing. Disjunct just means the notes are far apart from each other in pitch whereas conjunct melodies have notes that are fairly close together.

12) Understand And Practice Rhythm in Your Songs

At the very least, while you’re writing a song, you should be trying hard to make your rhythm sound musical. A steady rhythm is just as crucial as understanding different rhythms as well.

For instance, if you’ve taken my advice and you’ve recorded yourself, you may notice that you’re rushing through some parts and then going too slow through others.

As mentioned above, great rhythm comes from practicing with the metronome/drummer track and being adamant about it.

After you get a basic concept of how rhythm and timing works, try playing or singing along to different styles. Rhythms like Rock, Samba, Jazz, Blues, Salsa, etc. Having a basic understanding of different genres will open a lot of creative doors.

13) Learn How to Use GarageBand or Another DAW

You don’t have to learn everything about GarageBand to be a songwriter, but it will help a lot to know a little. Basic drum and instrument tracks can help you shape your ideas to become a better creator as you start implementing ideas in real-time using my tutorial to help you.

You can go back to songs and edit parts or add in practically anything you want with VSTs or samples via my guide.

Some people only use GarageBand to adjust audio tracks for videos or whatever they need audio for; if they can do that, they can edit a song with it too. It may not be the absolute best edit as if it was done in Logic Pro X, but a demo or an idea doesn’t have to be.

It just has to be recorded so that you can work with it. And it doesn’t stop there because you can use GarageBand to do a lot more as I’ve explained before.

14) Really Listen to Your Influences and Reverse Engineer Popular Songs

A great place to start in your musical journey is to listen to your influences. Play the parts, write down the lyrics, don’t just sing them.

Get a feel for song structure and lyrical content to help you along your songwriting journey. Joining a cover band or tribute band of your favorite artist may also help if you can sing or play an instrument. There’s a reason you love a particular band, they may hold the key that sets you off creatively.

Try their rhythms or chord progressions on your own, play them to spark ideas, or read their lyrics and go off of the same subject.

You don’t have to copy them unless you really want to disguise them as your own (many bands do!), The main goal is to spark interest and get ideas out there to work with. Pretty much every musician and songwriter ever learned how to make their own songs this way.

Try out websites like Songsterr and Ultimate Guitar Tabs if you cannot play by ear yet. From experience, Songster is way more reliable than Ultimate Guitar Tab, but let your ears tell you that.

It wouldn’t be a terrible idea to grab a copy of Guitar Pro 8 on Plugin Fox either because many of the best tabs/sheet music are in this format. Do yourself a favor and grab both the desktop and mobile versions – you can thank me later.

15) Learn Different Tunings, Chord Voicings & Scales, or Use a Capo

Different Tunings

If you are writing songs, you are probably using a guitar or piano. While the piano is an excellent tool for songwriting, the guitar is far more portable (and cheaper) which is part of the reason so many people start with one.

Joni Mitchell is one of the most iconic songwriters that often used unorthodox guitar tunings in her songs. In fact, she uses open tuning or alternate tuning more than standard, and it helped her write differently than others.

Use a Capo

With the use of a capo like this one, or even a spider capo, the tunings become even more complex and can be more interesting.

Learning how to properly use DADGAD tuning, Drop D, or even C# tuning will make music you already listen to make more sense. While the most common tuning found in recorded music is still standard tuning, it’s great to experiment and learn what sounds great to you.

New Chord Voicings and Scales

New chord voicings or even different extensions of some of the most popular chords is a great way to spark creativity.

Sometimes, all it takes is for me to hear a new chord or just see what it looks like on the diagram and I instantly grab for my guitar or my MIDI Keyboard.

Cool scales that I’ve never heard of before are the same way for me. For example, one of my favorite scales to play around with is the Harmonic Minor Scale. It’s a really interesting scale and even though it’s hard to make musical sense of it sometimes, particularly its modes, it sounds so cool to my ear.

16) Have Fun and Experiment With Nonsense

You can use music as a creative and emotional outlet in the most primitive sense.

What do I mean by that? For example, you could take a mic like the Zoom H6 into your closet and just scream into it and then load that audio recording into GarageBand over a hip-hop beat or a chord progression; add a bunch of effects to it, and then see what you can make out of it.

It’s stuff like this that really leads to innovative creations, and not only that, but it can be therapeutic.

Do you think Frank Zappa or Prince would have gotten where they were as songwriters and composers had they not experimented with anything and everything? Most likely, they wouldn’t have. Experiment, and if it doesn’t work, move on to the next thing.

17) Don’t Put Too Many Barriers On Yourself

Writing one song per day and consistently experimenting keep you from getting too attached to a song or idea. It can be the death of any artist to obsess over their own creativity.

Take liberations with it and keep making music. Don’t keep going back to the same thing if it doesn’t serve you anymore, move on and keep getting ideas out there.

As I already said earlier, if you’re putting barriers on yourself and being a perfectionist, eventually you’re going to suck the fun right out of it and then you simply won’t care anymore.

Don’t do this to yourself. Writer’s block is just another form of perfectionism. It’s the idea that whatever you’re doing isn’t good so you just scrap it. With all that in mind, let’s just wrap up what I believe are the key-take aways here.

1) Write a song every day using a popular chord progression

2) Learn the Key Signatures and the Major Scale

3) Use GarageBand or another DAW to record your ideas

4) Use GarageBand’s Drummer Track, Apple Loops, and other samples to fill in the gaps.

Gear Mentioned

1) Jazz Chord Mastery

2) Guitar Chord Progression Encyclopedia

3) Chord Progressions: Pick Up and Play

4) Mark Sarnecki’s Complete Elementary Rudiments

5) Mark Sarnecki’s Complete Elementary Rudiments – Answer Book

6) 11 Pro Max

7) MXR Clone Looper

8) Scarlett 2i2

9) Pro Tools

10) Guitar Pro 7.5

11) Capo

12) Spider Capo

13) Arturia Key Lab 61

14) Zoom H6

Written By :

Written By :